Last night in Platonic Love we discussed how Plato identified the motive of love for a beloved with the motive for wisdom, remembering after all that his practice was called ‘philosophy’, which literally means ‘love of wisdom’, love of Sophia.

Plato’s Symposium is one source of a tradition of mysticism where a powerful desire for Sophia drives the soul upwards towards the beloved first principle. When finally arriving at desireless union, the ego-self simply fades away.

In Christianity we might compare this erotic cult with that of the Mother-of-God (Theotokos), where her son was relegated to the role of emissary. This cult found expression in so much of the medieval art adorning all those huge solid Notre Dame (‘our lady’) cathedrals that once towered over the rickety tenements of medieval Christendom. But closer to Plato is the Judeo-Christian assimilation of Sophia as the divine medium (sometimes identified with the Logos) in the Wisdom Books, some of which remain in the Christian Bible. This Platonic motif would soon find monumental expression in the Hagia Sophia (‘holy wisdom’) basilica, which was built to mark the centre of imperial Christendom in Constantinople.

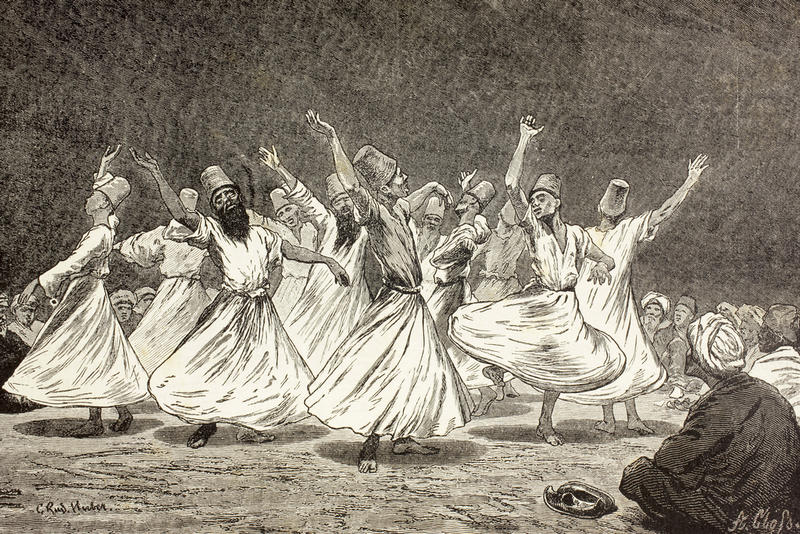

This erotic way of mysticism would also flourished in the Islamic East, in the Sufi’s enthusiastic desire for union with the divine. It’s re-entry into Christianity in this form was facilitated through southern Spain by one of the forgotten (and non-Aristotelian!) fathers of Western science, Ramon Llull, who published devotional guides like The Book of the Lover and the Beloved.